A brief history of wetsuits and how they work.

Wetsuits have only become part of surfing’s essential items list in recent years. Back when surfing was fledgeling tanned bods and bleach blonde hair was all you needed to score a decent surf sesh (and a board of course!). The fact that most of these riders were in warmer climes (with balmier water temps than the UK) helped. No need for thick rubber suits – or maybe surfers were just hardier back then?

Table of contents

Surfing’s migration

Surfing soon migrated though and a hotbed of surfing talent sprang up on California shores. While summers in Cali are (just about) warm enough for skin only board riding shenanigans winters can be much colder. And the further north you go the icier waters become (and remain) year-round. Therefore a solution was soon needed to fend off the chill.

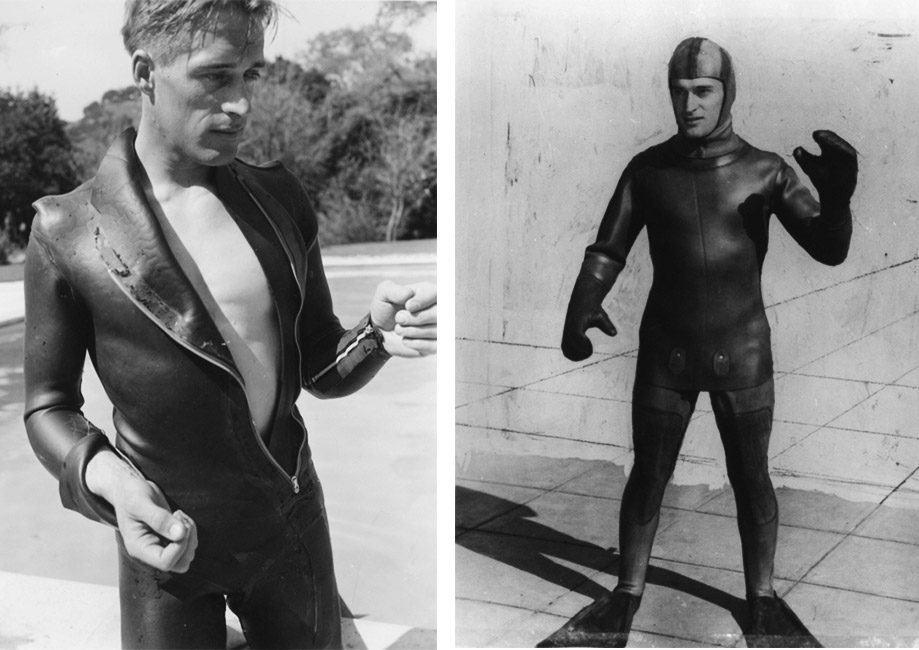

World War II salvage diving wetsuits

Wetsuits to combat the cold waters divers encountered can be traced all the way back to the 1910s. Salvage hunters, required to dive down great depths, needed a tool to halt hypothermia when immersed in cold water.

Looking more like a space suit the US Navy Frogmen – as they were nicknamed – was used extensively during World War II. It also served a secondary purpose of protecting against cuts and gashes when coming into contact with sharp objects. As for surfing, if ever anybody had tried to use a suit like this, they would’ve probably given up in frustration due to lack of mobility and inefficient insulation.

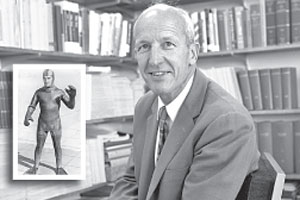

Hugh Bradner and modern wetsuits

Hugh Bradner, looking to improve on the wetsuit design above, came up with his own version around 1951-52. Sandwiching thin neoprene layers between nylon and spandex the suit trapped water between the wearer’s body, which in turn warmed up during movement, and therefore halted cooling from outside water surrounding the wearer.

The patent Bradner filed was rejected after it being deemed too close in similarity to a flight suit. Upon presenting it to the US Navy they too turned it down with reasoning given that inherent gas within neoprene was more visible to enemy sonar and therefore detection.

Jack O’Neill and influence on wetsuit design and development

Hugh Bradner, hearing about Jack O’Neill’s search for an efficient way of fending off cold water, took his wetsuit to showcase its properties to the man in Santa Cruz. O’Neill was manufacturing early neoprene wetsuit from his garage. Nicknamed the ‘beaver tail’ Jack’s first suits looked particularly whacky with a dangling piece of rubber swinging between the wearer’s knees.

At a similar moment in time Body Glove owner Bob Meistrell also began manufacturing similar styled wetsuits. Unfortunately, many of these first wetsuit types were fragile and would often rip and tear. This led to materials such as nylon being added which would make them more robust.

Up-to-date, modern wetsuits

Following those early developments, the front zip moved to the back with this being more efficient and less prone to flushing. Two-piece suits weren’t exactly efficient and were replaced very quickly by all in one wetsuits pioneered by Gul Wetsuits in the early 70s. Gul’s one-piece suits were nicknamed ‘steamers’ because of the heated water held inside only escaping once the wearer removes it. The quick evaporation warm water turned to steam. To this day the nickname stands and is used to describe one-piece winter wetsuits. In fact, here at NCW we have a Gulf Stream Steamer line of wetsuits which you can see in our online shop.

These days the technology surrounding wetsuits is right up there. One of the biggest revolutions with wetsuit design was the introduction of taped seams. Made from super-tough nylon a seam is layered across the stitched area and bonded with chemical solvent or heat sealer. This makes wetsuits extremely strong as well as providing some extra insulation.

Following this, each seam along a wetsuit’s panels is flatlocked and glued creating and smooth and flat surface that improves comfort and efficiency. This also helped hugely with sizing inaccuracies. A lot of early suits were notoriously difficult to get right in terms of size.

Further advancements with wetsuit development

Wetsuits these days utilise some pretty exotic materials to improve things like elasticity, without compromising the original aim of what a wetsuit’s job is. Fleece liners, wool and spandex are used to good effect in wetsuits, although not limited to just these materials.

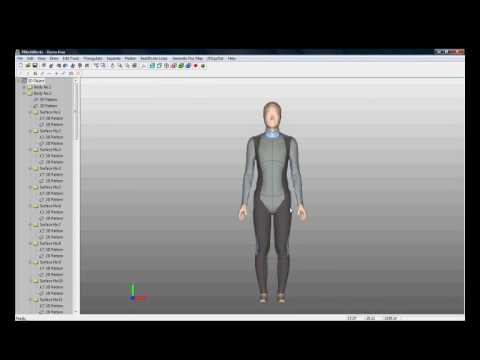

CAD design and laser cutting of wetsuit panels and the way they’re laid up are all standard practice these days. Some water disciplines, that rely on efficiency through the air, as well as water has called for improved aerodynamics and reduction in drag. As such features which help this kind of thing can be found incorporated into relevant wetsuits.

Also, with improvements in blindstitching and elastic Lycra backings single-backed wetsuits can now outperform early 70s suits considerably. And then there’s, of course, the aesthetic aspect. Wetsuits now come in all kinds of colours of hues and can be custom-made to a wearer’s exact specifications.

How wetsuits work

In a nutshell, as with the original pioneering wetsuit designs of old, a neoprene suit traps a thin layer of water between the wearer’s body and the suit’s material. As the wearer (in this case surfer) moves body heat generated helps warm the water up and the whole thing acts like a mini central heating system. Add to this the layering properties of a wetsuit and you have a super-efficient, protective barrier against cold water on the outside.

Not all wetsuits are the same, however, with many having different numbers of layers and materials these layers are made from – hence why we have wetsuits applicable for different conditions and different seasons.

That said, in theory, a super warm wetsuit should be made up of components of the following –

- The wearer’s skin.

- A thin layer of water trapped and warmed by the rigorous movement of the wearer.

- A layer of comfortable neoprene that doesn’t chafe or rub.

- Heat-reflecting material that has metal oxide properties such as titanium, copper, silver, magnesium or aluminium. Titanium inner liners are popular in wetsuit design.

- A thick layer of neoprene that has tiny bubbles of nitrogen contained within is the most important part of the wetsuit for actually keeping you warm.

- Some form of durable outer layer that’s resistant to scrapes and scuffs.

Wetsuit fit

Any wetsuit needs to fit correctly for it to work properly. Water that seeps in ultimately has to remain there. Continual flushing of cold water will see the surfer cool significantly possibly bringing the onset of hypothermia.

In conclusion

A wetsuit should be snug around all areas of the body, particularly the lumber and core areas where considerable loss of body heat can occur. Seams, such as ankle, wrist and neck also need to be efficient and prevent flushing as much as possible. For particularly cold environments a hood, gloves and boots can be added to further aid protect against water flush and heat loss.

Wetsuits have come a long way over the years and they’re the one really necessary piece of gear for surfers and all watersports enthusiasts practising their chosen discipline in cooler water like those found in the UK.